Below: A selection of modern Ethiopian coins, 1903-2008 Ethiopian coins can be hard for a beginner to identify, as they use a non-Western script. Even the numbers for the dates and denomination may only be given in Ge’ez numerals. One common feature is that Ethiopian coins will almost all have a lion. For older coins, during which Ethiopia had an emperor, the Lion of Judah (a lion carrying a scepter with a cross diagonally) appears on the reverse, signifying the legendary Solomonic origins of the Imperial Family. For modern coins of the Communist government or the subsequent Republic of Ethiopia, the lion will appear as a large lion’s head on the obverse.

Ethiopian coins can be hard for a beginner to identify, as they use a non-Western script. Even the numbers for the dates and denomination may only be given in Ge’ez numerals. One common feature is that Ethiopian coins will almost all have a lion. For older coins, during which Ethiopia had an emperor, the Lion of Judah (a lion carrying a scepter with a cross diagonally) appears on the reverse, signifying the legendary Solomonic origins of the Imperial Family. For modern coins of the Communist government or the subsequent Republic of Ethiopia, the lion will appear as a large lion’s head on the obverse.

Once you have narrowed a coin down as likely coming from Ethiopia, there are free online resources one can use to compare to the coin. For example, a search for coins from Ethiopia on Numista gives only 4 pages of results, so it’s not too time consuming to look for a match by hand. One caveat is that several coins look very similar. One may need to check the weight and diameter to see which one you have. For example, the 1944 series of 1, 5 and 10 santeem are shown below.

All of them have a bust of Emperor Hailé Selassié I on the obverse, along with the date ፲፱፻፴፮ (1936 by the Ethiopian calendar, which is 1944 in the Western calendar). The reverse has a Lion of Judah with the denomination spelled out in Amharic script: either 1 (አንድ:ሳንቲም), 5 (ለምለት:ሳንቲም) or 10 santeem (አሥር:ሳንቲም). Modern Amharic is written from left to right, in spite of it being a Semitic Language, of the same family as such right-to-left languages as Arabic and Hebrew. If you weigh them, they are approximately 3, 4 and 6 grams of copper for the 1, 5 and 10, respectively.

All of them have a bust of Emperor Hailé Selassié I on the obverse, along with the date ፲፱፻፴፮ (1936 by the Ethiopian calendar, which is 1944 in the Western calendar). The reverse has a Lion of Judah with the denomination spelled out in Amharic script: either 1 (አንድ:ሳንቲም), 5 (ለምለት:ሳንቲም) or 10 santeem (አሥር:ሳንቲም). Modern Amharic is written from left to right, in spite of it being a Semitic Language, of the same family as such right-to-left languages as Arabic and Hebrew. If you weigh them, they are approximately 3, 4 and 6 grams of copper for the 1, 5 and 10, respectively.

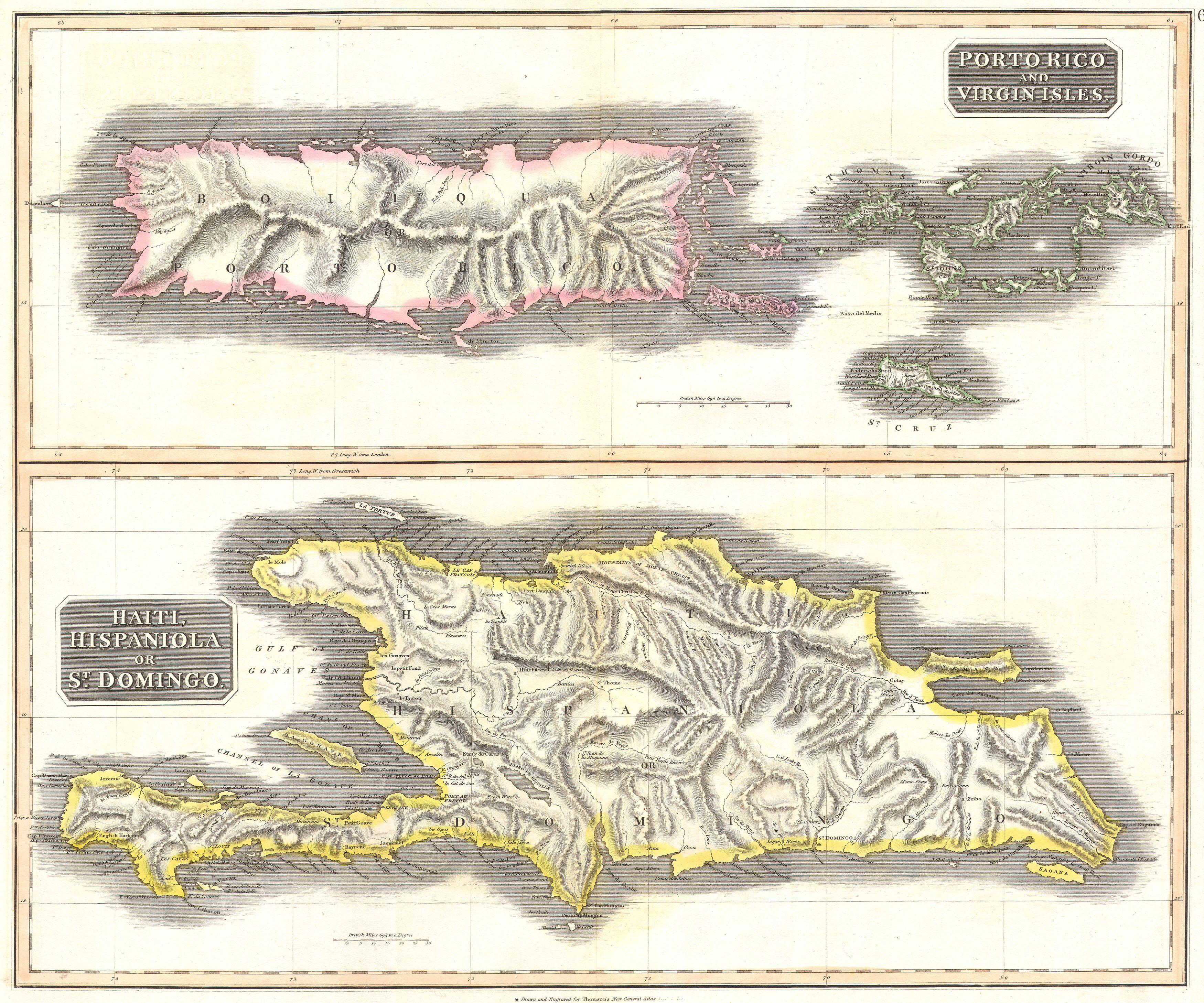

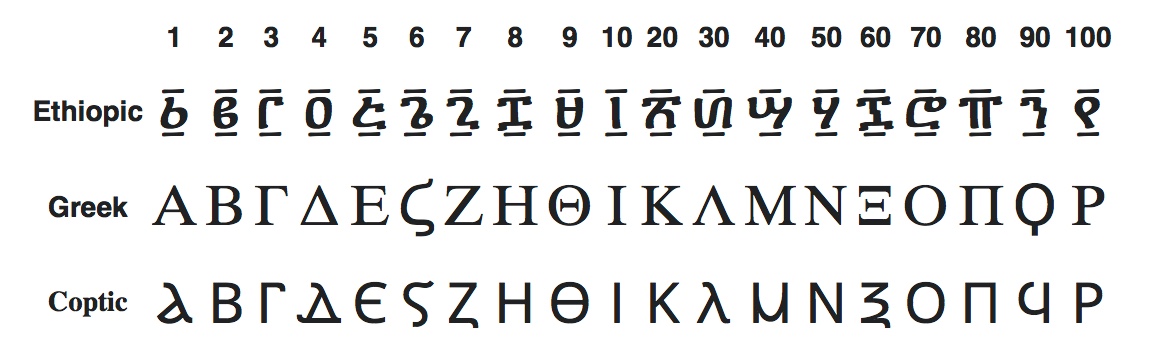

Reading dates is a bit tricky. Amharic numerals are derived from Ancient Greek numerals, in which the first 9 letters represent the digits 1-9, the next 9 for the numbers 10-90, and the last 9 for numbers from 100-900. In that way, three letters can be used to write any letter from 1 to 999. The Greek alphabet only has 24 letters, so 3 obsolete letters: stigma (Ϛ), koppa (Ϙ) and sampi (ͳ), are needed to have enough letters for a full three digits. Though the concept of zero existed, no separate numeral for zero as a place value holder had been invented yet.

Above is a table borrowed from Wikipedia showing how numerals in the Ethiopian Ge’ez script evolved from Ancient Greek via Coptic. Unlike in Greek, Ethiopian numerals end with 100. Larger numbers are written as multiples of 100 followed by the numeral for 100, ፻. A doubled 100 character (፼) represents 10,000s. To distinguish numbers from letters, numbers have lines written over and under them. If numbers are spelled out in Amharic rather than using numerals, though, the lines are not used.

Above is a table borrowed from Wikipedia showing how numerals in the Ethiopian Ge’ez script evolved from Ancient Greek via Coptic. Unlike in Greek, Ethiopian numerals end with 100. Larger numbers are written as multiples of 100 followed by the numeral for 100, ፻. A doubled 100 character (፼) represents 10,000s. To distinguish numbers from letters, numbers have lines written over and under them. If numbers are spelled out in Amharic rather than using numerals, though, the lines are not used.

Going back to the 1944 copper coins pictured above, we now have enough information to decode the date, ፲፱፻፴፮. These are the numerals for 10, 9, 100, 30 and 6 in order, representing (10+9)*100+30+6 = 1936. Though the Ethiopian calendar is a Christian one, it calculates a different start date for the Annunciation of Christ. The Ethiopian year starts around September, so one needs to add 7 or 8 years to the Ethiopian year to get the equivalent Western AD date. These copper coins are thus all dated 1944 AD.

As a side note, the Ethiopian Calendar has leap years every 4 years without exception for 100/400 year corrections. And the leap year cycle is named rotating through the 4 Evangelists. So this year (2020) would be a Luke year, followed by a John, Matthew and Mark year in a 4 year cycle.

Now that we can read off dates, let’s look at some older coins.

The left coin is a bit worn and hard to make out, but the date is ፲፰፻፺፩, 1895 = 1903 AD. It is a silver 1 gersh, from a pre-decimal monetary system in which 20 ghersh = 1 birr. The Emperor on the face is Menelik II. The righthand coin is dated ፲፱፻፳፫, 1923 = 1931 AD. It is a nickel 25 matonas of Emperor Hailé Selassié I. Unlike the more recent copper coins shown earlier, the Emperor is shown with his crown instead of bareheaded in a Western-style suit. Next are 4 coins from the Communist and modern eras.

The left coin is a bit worn and hard to make out, but the date is ፲፰፻፺፩, 1895 = 1903 AD. It is a silver 1 gersh, from a pre-decimal monetary system in which 20 ghersh = 1 birr. The Emperor on the face is Menelik II. The righthand coin is dated ፲፱፻፳፫, 1923 = 1931 AD. It is a nickel 25 matonas of Emperor Hailé Selassié I. Unlike the more recent copper coins shown earlier, the Emperor is shown with his crown instead of bareheaded in a Western-style suit. Next are 4 coins from the Communist and modern eras.

From L to R and top top bottom:

5 Santeem, Brass, Derg Socialist Junta, ፲፱፻፷፱ 1969 = 1977 AD

10 Santeem, Brass, Derg Socialist Junta, ፲፱፻፷፱ 1969 = 1977 AD

25 Santeem, Nickle-plated Steel, Republic of Ethiopia, ፪ሺህ 2000 = 2008. The date is given as the numeral 2 (፪) followed by the word thousand (ሺ = ši) spelled out.

50 Santeem, Cu-Ni, Derg Socialist Junta, ፲፱፻፷፱ 1969 = 1977 AD

Coins from before and after the fall of the Communist regime generally use the same designs. One can use the dates to tell which era they came from. Some coins changed material from brass to brass-plated steel in the post-Communist era. They can be differentiated by the dates, or because the plated steel ones are attracted to a magnet.

Ethiopian coins can be hard for a beginner to identify, as they use a non-Western script. Even the numbers for the dates and denomination may only be given in

Ethiopian coins can be hard for a beginner to identify, as they use a non-Western script. Even the numbers for the dates and denomination may only be given in

All of them have a bust of Emperor Hailé Selassié I on the obverse, along with the date ፲፱፻፴፮ (1936 by the Ethiopian calendar, which is 1944 in the Western calendar). The reverse has a Lion of Judah with the denomination spelled out in Amharic script: either 1 (አንድ:ሳንቲም), 5 (ለምለት:ሳንቲም) or 10 santeem (አሥር:ሳንቲም). Modern Amharic is written from left to right, in spite of it being a Semitic Language, of the same family as such right-to-left languages as Arabic and Hebrew. If you weigh them, they are approximately 3, 4 and 6 grams of copper for the 1, 5 and 10, respectively.

All of them have a bust of Emperor Hailé Selassié I on the obverse, along with the date ፲፱፻፴፮ (1936 by the Ethiopian calendar, which is 1944 in the Western calendar). The reverse has a Lion of Judah with the denomination spelled out in Amharic script: either 1 (አንድ:ሳንቲም), 5 (ለምለት:ሳንቲም) or 10 santeem (አሥር:ሳንቲም). Modern Amharic is written from left to right, in spite of it being a Semitic Language, of the same family as such right-to-left languages as Arabic and Hebrew. If you weigh them, they are approximately 3, 4 and 6 grams of copper for the 1, 5 and 10, respectively. Above is a table borrowed from Wikipedia showing how numerals in the Ethiopian Ge’ez script evolved from Ancient Greek via Coptic. Unlike in Greek, Ethiopian numerals end with 100. Larger numbers are written as multiples of 100 followed by the numeral for 100, ፻. A doubled 100 character (፼) represents 10,000s. To distinguish numbers from letters, numbers have lines written over and under them. If numbers are spelled out in Amharic rather than using numerals, though, the lines are not used.

Above is a table borrowed from Wikipedia showing how numerals in the Ethiopian Ge’ez script evolved from Ancient Greek via Coptic. Unlike in Greek, Ethiopian numerals end with 100. Larger numbers are written as multiples of 100 followed by the numeral for 100, ፻. A doubled 100 character (፼) represents 10,000s. To distinguish numbers from letters, numbers have lines written over and under them. If numbers are spelled out in Amharic rather than using numerals, though, the lines are not used.

The left coin is a bit worn and hard to make out, but the date is ፲፰፻፺፩,

The left coin is a bit worn and hard to make out, but the date is ፲፰፻፺፩,